A lengthy excerpt from my Autobiography covering graduating RMA and my experiences in the US Navy. Covers Chapters 23-31 or so.

Chapter 23: Mountain State University to Orlando NTC

A Frostburg Beginning

After graduating high school, I embarked on my collegiate journey with a full academic scholarship to Frostburg State University, located in the scenic mountains of Western Maryland—an institution that also inspired Greg Garcia of "My Name is Earl." Embracing the life of an engineering major, I became part of the rugby team, diving into a lively social scene. However, the structured discipline and warmer climate of Orlando, the home of Naval Nuclear Power School, presented a compelling contrast, motivating me to join the Navy after my first semester.

The Pontiac 6000: Lessons in Responsibility

Graduating high school brought an interesting twist: my parents, striving for a sense of fairness, bestowed upon me their aging, puke-green Pontiac 6000 Station Wagon. This was the same vehicle that Linda, my stepmother, had driven for the better part of a decade before it was ceremoniously handed down to me. It may seem petty to note—given the privileges I already had—that during our high school years, my stepsister Katherine received a Nissan NX1600, which she eventually totaled in an accident, the details of which remained a mystery to me. The aftermath of her accident was met with what I perceived as a reward: she was given a reliable Saturn SL2 and took over the entire basement area of our house, a domain where I became unwelcome.

I went on to equip this Pontiac 6000 with a robust custom stereo system, marking the beginning of a series of expertly configured 12-volt car audio installations and the continuation of my passion for loud, high-fidelity music. Regrettably, I was oblivious to the importance of regular vehicle maintenance, most critically, oil changes. On a solitary drive back to Frostburg from the local skating rink, the car abruptly died, and the engine refused to restart. A local mechanic, nestled in the steep valleys of the surrounding area, managed to replace the defunct engine with a used one for $795.00.

Also worth mentioning is that upon my graduation, my grandparents Vassie gave me a considerable number of immature savings bonds. The intention behind this generous gift was to teach me the value of saving and how it could multiply one's wealth. However, lacking financial foresight, I quickly depleted these bonds to pay for the new engine and to indulge in wedge-shaped, Philly-style pizzas from a favorite local eatery.

Influences and the Decision to Enlist

During this time, I had a significant conversation with Pete Linzmeyer, my senior-year roommate from RMA, who had recently returned from Army boot camp. His description of the demanding military life resonated with me, reinforcing my decision to enlist. Separately, my brother’s high school friend Charlie Benson had recently graduated from Nuclear Power School and gave me the low down on the challenges, and rewards, of enlisting in the Navy as a Nuclear operator.

In parallel to these academic and military aspirations, I faced a personal challenge with weight management. A short stint as a pizza delivery driver led to a rapid weight gain—from 195 to 235 pounds. The Navy provided a stark change in routine, and by the end of boot camp, I had shed a remarkable 60 pounds. This cycle of weight loss and gain was not new to me; during my junior and senior years of high school wrestling, I experienced similar fluctuations. This ongoing battle with weight is a thread that weaves through the narrative of my life, a consistent struggle that endures.

My time at Frostburg State University was a period of real despondency. I remember the excitement of arriving at the school and unpacking my giant stereo system, consisting of a mid-level Onkyo Tuner Amplifier, a sophisticated Rube Goldberg 6-disc changer Onkyo component CD player, an equally sophisticated matched Onkyo dual tape deck, and JBL L60T speakers. I had always been an audiophile with an enormous collection of CDs spanning a broad range of tastes, including Kitaro, Yanni, Yes, Yaz, The Cure, Depeche Mode, Ministry, Nitzer Ebb, Guns N’ Roses, Metallica, John Williams and the Boston Pops, the Glenn Miller Orchestra, Jazz, Classical, Nature Sounds, Deep Forest, and early dance hits like Dance Mix USA, which would evolve into my passion for EDM, among other things— notably how DJ Doboy's Vocal Editions would become one of the most popular genres of music today.

Rugby

And then there was rugby. I don't know why I didn't try to walk onto the football team. I didn't have or even attempt to obtain an athletic scholarship, but one thing that I think would have changed the entire trajectory of my life would have been just to walk onto the team and give it my best shot. Instead, partly because it was the only social grouping I could join in my freshman semester—Frostburg outlawed freshman fraternity rushing—I joined the Rugby Team. So, I paid my $45.00 dues and in exchange obtained a cool rugby jersey and, more importantly, a free pass to daily drinking events. The rugby team maintained a party house just off campus, and I recall many a drunken afternoon shouting Bob Marley's "Don't worry..." with the whole team.

Shoot the Boot!

In one memorable episode at the local restaurant we regularly frequented together, one of the senior members challenged me to a dare: drink from his boot. This was disgusting, but I was super intoxicated and not one to back down from a dare. The senior member of the team took off his boot, and to cheers of "Shoot the Boot! Shoot the Boot!" I guzzled down a bootful of beer. At the house a short time later, this motif of drinking from disgusting things was replicated. The same team member challenged me to drink from the plunger. This was thoroughly disgusting, and at first, I was like, "NO F'ING WAY!!" But then the senior took the plunger, topped it off from the keg, and proceeded to down the whole thing. Then triumphantly, he handed a topped-off plunger to me and, with steely eyes, commanded, "DRINK!" I had no choice and downed it to the cheers of my teammates and Bob Marley wailing in the background.

Playing Rugby Against the Naval Academy!

Ironically, my physical fitness dropped off rapidly during this time. I experienced tremendous weight gain even though I avidly skated the hilly campus as regularly as I could several days a week. I recall in particular one rugby match where we played the US Naval Academy's C squad rugby team. Their C squad, meaning they had two better teams than this! They cleaned our clocks, but in the end, we all partied together that night, and fortunately for the Naval Academy lads, our female rugby team provided what I can only imagine was more intimate care than we did on the

A small but notable part of my college life was joining the school's intramural hockey team. I owned a pair of Bauer hockey skates, which I had previously used only during public skating sessions at different ice rinks. Although I had some experience playing organized roller hockey in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware, two summers prior, I had never played organized ice hockey before. Regrettably, my memories of these games are marred by breathlessness and frustration; by the time I joined the team, I had become significantly overweight and my cardiovascular fitness was poor, which greatly hindered my performance on the ice.

Adventures with Dave Laime

On Halloween Weekend, Dave Laime, who I talked to frequently through this time, gave me a call one Thursday afternoon and asked me if I wanted to go on a road trip. Without needing to check my calendar, I enthusiastically accepted. About six hours later, he arrived in Frostburg with his mom's trusty 1980's vintage Honda Civic and with barely $40.00's between us, hit the road for Columbus, Ohio where a girl he had met at the beach the prior summer was attending Ohio State University. So we drove the whole way, smoking generic cigarettes, singing along to Ball and Chain and Story of My Life by Social Distortion all the way. We picked up his girlfriend, then headed down to Athens for the renowned OU Halloween observances where we met up with his girlfriend's girlfriend and enjoyed the festivities. On a separate weekend, we went to Radford and Virginia Tech for a notable weekend of youthfull fun and somewhere else to ODU in Richmond.

Through it all, my fondness for cars remained a constant source of joy. Even my puke-green Pontiac 6000 Station Wagon was an oasis of sorts, its impressive stereo system transforming each delivery into a mini-concert experience. This car, and later traded for a $14,500.00 red 1990 Geo Storm GSI, were more than just transportation; they were sanctuaries on wheels, complete with all the shiny buttons and features that brought me happiness, no matter where the road took me. Nowhere else could I find the shear joy of being able to control every aspect of my environment. Too cold, dial the AC down. In a sad mood, pop in some classical music, or Depeche Mode or a Letter to Elise. On the go? How about some Ministry, Nitzereb, Thrill Kill Cult.

In the early morning hours of January 8, 1991, I was driving home from my job delivering Dominos Pizza where I coincidentally gained roughly 25 lbs, when I failed to come to a complete and full stop at a blinking red light at 1:30 AM. Fortunately, there was a vigilant police officer 'manning' this notorious intersection of death even at these early, empty hours, protecting the slumbering citizens of Montgomery County from evil stop light not stoppers. I'm just saying there wasn't a car on the road in any direction. The officer who pulled me over noted that there had been a number of fatal accidents at this intersection and she felt it was her duty to correct my abhorant behavior. Thus I recieved my first moving violation which required a tremendous amount of paperwork the next day at MEPS and ultimately ended up costing me at least 10 K of increased insurance premiums.

Chapter 24: Bootcamp and NTC Orlando

Departure from Frostburg

On January 9, 1991, I left Frostburg, Maryland, behind and drove to my recruiter’s office. From there, we took a General Motors government vehicle to MEPS (Military Entrance Processing Station) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I was accompanied by a few other recruits, including a female who would later go on to corpsman school. She and I stayed in contact, and our paths would cross again years later when I was stationed in Norfolk.

MEPS: The Bureaucratic Gauntlet

That day at MEPS was consumed by medical exams, paperwork, and waivers—including ones for my second-grade psychiatric hold at 4 Orange in Washington Children’s Hospital and a recent moving violation that nearly cost me my enlistment. It was all business, all day.

The night before we officially processed, the Navy put us up in a mid-tier motel. I still remember talking and flirting with that same female recruit, sharing the electric anticipation of stepping into a new life. In the end, she picked someone else, but we kept in touch. That brief connection, and the unspoken nervous excitement among the group, made the experience feel almost cinematic.

Welcome to RTC Orlando

The flight to Orlando is a blur. What I remember with total clarity is the humiliation of the urinalysis upon arrival. We were herded into a gymnasium-sized room with masking tape on the tile floor, lined up like cattle, and ordered to pee while staff watched from behind. I froze. Despite repeated commands, jabs, and marching drills to “encourage” performance, I couldn’t go. My personal pee shyness kicked in hard. It took me hours of pacing, hydration, and shame before I could finally deliver a sample—at approximately 3:30 AM.

My reward? Barely an hour of sleep before being jolted awake by drill instructors hurling a metal trash can down the center of the barracks. Welcome to Navy Boot Camp.

Wax On, Wax Off – Navy Style

What makes Navy Boot Camp unique isn’t just the physical training, but its obsession with detail. Locker folding was an art form. Each garment had to be pressed, aligned, and folded to precise measurements—basically military origami. Then came Locker Drills, where we were ordered to dump every perfectly folded item onto the deck and refold it under timed conditions while instructors barked corrections.

Every moment had purpose. Even the language had to change. We didn’t walk—we marched. We didn’t drink water—we drank from the scuttlebutt. We cleaned the deck, stowed our gear in lockers, and stood silently next to the bulkhead. We weren't in a hallway—we were in a passageway. The Navy has its own dictionary, and by the end of week one, you’d better be fluent.

The Grinder and Galley

Every day, we assembled on The Grinder—a massive slab of concrete where we practiced marching, performed PT, and waited to be marched to meals. Compared to the robotic precision of Air Force JROTC, Navy marching style had swagger. That swagger was encouraged and reinforced during cadence drills, where we added a bounce and rhythm foreign to my old RMA habits.

Each morning, we stood motionless in ranks, inching forward across the Grinder toward the galley. Once inside, we waited silently. Meals were quiet, efficient, and completely joyless. I refused to eat. Whether it was depression, disgust, or just the way my body processed stress, I literally ate nothing for the first four weeks. I likely lost 30 pounds during that time.

The “Fat Boy” Program

When I arrived at boot camp, I weighed in at a husky 235 pounds—largely the result of my pizza delivery phase and sedentary lifestyle prior to enlistment. This put me squarely into what we informally called the “fat boy program.” The official designation didn’t matter much—everyone called it that. The deal was simple: do extra PT voluntarily on your own time, before the rest of the company was even awake, or risk falling behind in the Navy’s physical readiness standards.

So, every morning at 0330, I was up and on the Grinder—the enormous slab of concrete where we trained and assembled. Alone under the floodlights, I pounded out sets of push-ups and sit-ups, followed by a five-mile run around the perimeter. It was grueling and lonely, but it worked. The rest of boot camp had its scheduled PT, of course, but it wasn’t consistent or intense enough on its own to get me back into Navy shape.

By the time I graduated boot camp, I had lost 65 pounds, dropping from 235 down to 170 pounds. I needed an entirely new set of uniforms, as the original ones I’d been issued practically hung off me. I’d slimmed down so much that people I’d trained alongside for weeks didn’t recognize me at graduation.

The 50 State Flag Team

Somewhere amid the early-morning PT, the folding drills, and the constant pressure, I was selected to represent our company on the 50 State Flag Team. RTC Orlando had two ceremonial units: the Unarmed Drill Team and the 50 State Flag Team. The flag team was especially sought after for one important reason—it was the only activity that allowed male and female recruits to train together. In a sea of gender-segregated barracks, PT sessions, and day-to-day duties, this was a major social opportunity.

Each day, I would muster with the flag team for marching rehearsals, precise formations, and ceremonial duties. It gave me a mental break from the monotony of boot camp and the pressure of inspections and drills. But more importantly, it was during this time that I met a girl I genuinely liked—smart, poised, grounded. We clicked in a way that felt rare in the high-stress, highly controlled boot camp environment.

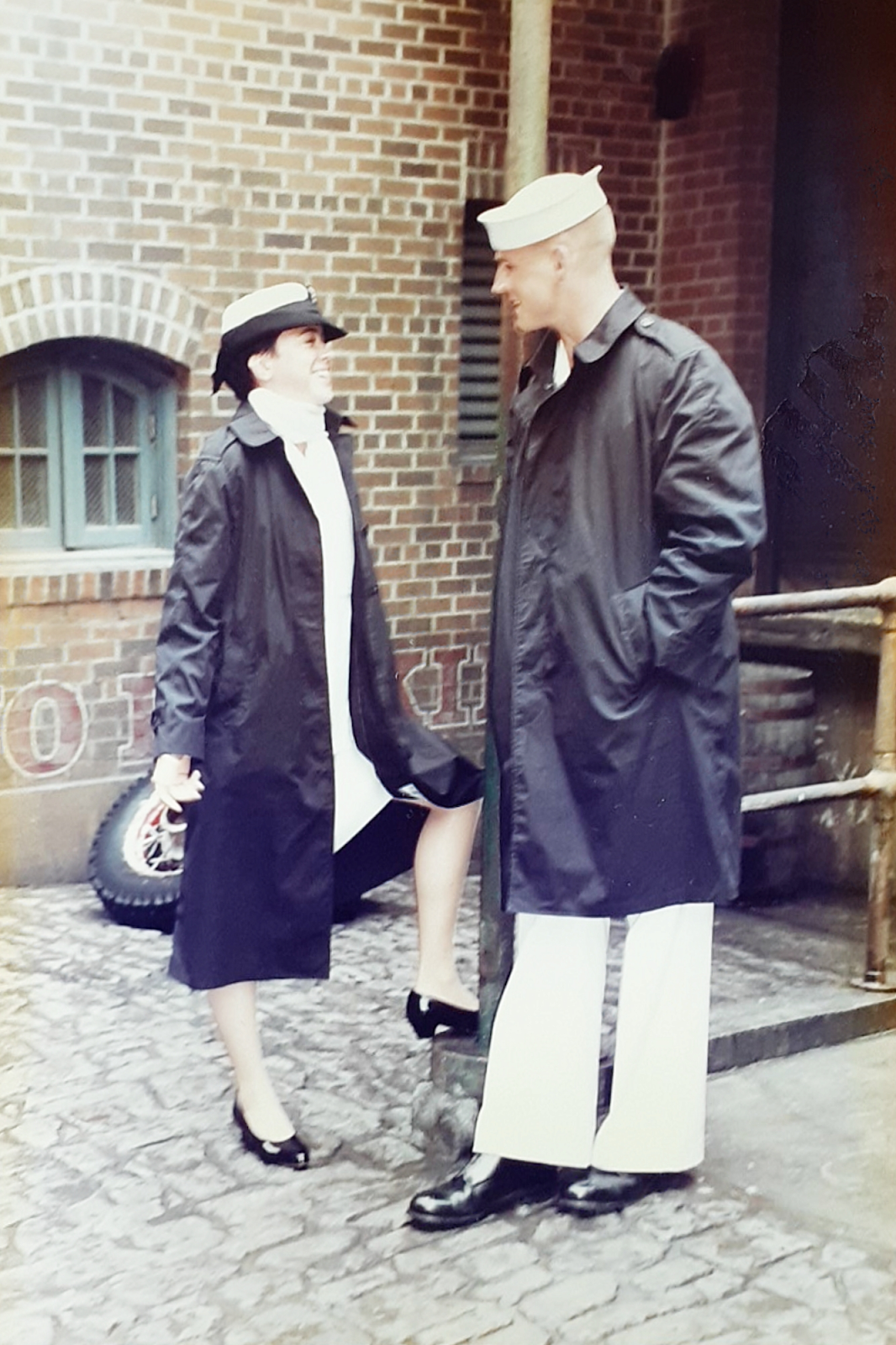

We never officially dated—boot camp rules made that impossible—and after graduation, life moved us in different directions. She joined me and my family for a day at Universal Studios during liberty following graduation, and we took a few incredible photographs together, full of optimism and light. But as was often the case in my life at the time, the thread of connection was severed prematurely—my father lost his black address book, the only place where her contact information was written. No phone number, no last name committed to memory. She became one of those perfect “what if” chapters that closes before the next page even begins.

Mind Games and the Line

Boot camp wasn't just physical—it was deeply psychological. The instructors were masters of the mind game, and one particular evening stands out like a training scar etched into memory. Chief Whitehead and our First Class Instructor marched in just after evening chow. We knew something was coming—their expressions had that telltale “we’re about to break you” look.

This time, it was a locker drill.

We’d been through dozens by now. Dump everything on the floor, fold it back perfectly to spec, get it inspected, then start over. This time, though, there was a twist. Chief Whitehead stood front and center and laid it out:

“This is going to be the most brutal inspection yet. If anything is out of place—one jot, one iota—you’ll be dropped to do eight-count bodybuilders until you collapse. Then we’ll reset, and you’ll do it again. And again. So, if you’re not absolutely confident, save yourself the shame—step to the outside of the bunks.”

The barracks had two rows of bunks, lockers on the inside facing a tile line where we were expected to place our toes. That line was the crucible—the commitment. Step off, and you were spared... or so it seemed. Stand firm, and you faced the wrath of the most intense locker inspection imaginable.

It was clearly a trap—a confidence drill, a test of mental fortitude. I saw it immediately. I stayed on the line. One by one, others peeled away. Even our Recruit Company Commander stepped off, eyes down, pride evaporated. In the end, only four of us out of 82 recruits remained, standing silently with our toes on that line.

Chief Whitehead looked us over with a sly grin and said:

“This is it? These are the only ones who think they’re ready?”

Then, with a dramatic pause:

“Alright, you four—at ease. Everyone else? Get into the Lounge.”

The Lounge was a relic from a forgotten era—a multipurpose room tucked behind the barracks that we’d never actually used except for this moment. It was massive when empty, but with 78 recruits crammed in, it became a furnace of misery. From our racks, we could hear them: the moans, the groans, the nonstop PT. Push-ups. Sit-ups. Running in place. Eight-count bodybuilders until the walls sweated along with them.

For two hours, the pain echoed off the tile floors and cinder block walls. It was glorious. Not because of their suffering—but because we’d passed the test. The point of the exercise was never locker perfection—it was mental toughness, belief in yourself under pressure, even when surrounded by fear and doubt. And the line... the line had separated those who folded from those who didn’t.

It was one of the proudest moments of boot camp for me.

Graduation and a Family United

Upon graduating from boot camp, there was a rare and moving coming-together moment in my family—a moment of pride that transcended the usual tensions and fractures. Among the attendees was the man who had inspired me more than perhaps anyone else: my grandfather, Harry B. Vassie.

Seeing him there, standing at attention as we marched in formation, filled me with immense pride. This was no ordinary man—he was a World War II veteran who had served as an airdales crewman aboard the legendary CV-5 USS Yorktown, a ship that played a pivotal role in the Battle of Midway, one of the most decisive victories in naval history.

His service during the war was only the beginning. After the conflict, he earned a college degree and returned to the Navy, this time as an officer in Naval Intelligence. Later, he transitioned into one of the most secretive arms of the U.S. government—the National Security Agency (NSA)—where he worked through the height of the Cold War. To this day, the exact nature of his service at the NSA remains shrouded in mystery. True to the values he held sacred, my grandfather never broke his oath of secrecy, not even near the end of his life.

A few short months after my graduation, he passed away. He never spoke about the classified details of his intelligence work, but he did let me know, with unmistakable clarity, how proud he was of me for continuing the family’s tradition of service. His stoic integrity, quiet brilliance, and deep sense of duty left a mark on me that has never faded.

My decision to join the Navy wasn’t just a reaction to life circumstances—it was a direct legacy of the man who had stood tall through one of history’s most perilous conflicts, who had moved silently through corridors of secrets in defense of the nation, and who had modeled what it meant to serve with honor and discretion.

Standing there at RTC Orlando, the Navy's version of graduation caps flying in the Florida sun, I didn’t just feel like a new recruit. I felt like I had stepped into the current of something larger than myself—a continuation of my grandfather’s story, and perhaps one day, a torch I might pass on.

A-School and a New Chapter in Orlando

After the formalities of boot camp and the deeply moving family reunion at graduation, I began the next phase of my Navy journey: Machinist’s Mate “A” School at Naval Training Center Orlando. The program was 16 weeks of intense, nuclear-focused mechanical training—grueling in pace and precision. It was here that we were expected to learn the language of machines, and by the end of it, operate and maintain the vital propulsion systems of America’s most advanced naval vessels.

Success in A-School came with its rewards. Upon graduation, I was automatically promoted to Machinist's Mate 3rd Class (MM3), which placed me at E-4 on the pay scale. This wasn’t just symbolic—it was financial. Unlike E-3s, E-4s were eligible for sea pay and submarine pay, a detail that might seem minor but would become relevant in the months to follow.

Amber and the Geo Storm

It was also during this chapter—somewhere between classroom drills and cross-sectional schematics—that I had a fateful encounter at a stoplight on Colonial Boulevard in Orlando, sitting behind the wheel of my red 1990 Geo Storm GSI. My car bore a Just Blow Me Surfwax Bubble Gum sticker on the side—irreverent, sure, but somehow a conversation starter. That’s how I met Amber Goettig.

Amber and I hit it off almost instantly. We dated for about six months, and during that time, she became a semi-permanent resident at my grandparents' house in Palm Harbor, which sat on a canal off Lake Tarpon. My grandmother didn’t seem to mind—at least not outwardly—and we slipped into a kind of routine that felt, at times, almost domestic.

Funeral and Family Crossroads

Amber was by my side when my grandfather passed away just months after attending my boot camp graduation. She stood with me at the funeral, a difficult and heavy day that carried the weight of both grief and legacy. That she was present meant something, even if what came next left an unexpected impression on the family.

During the post-service gathering, Amber rode with my Aunt Abbey in the family limo. I wasn't there for the conversation that unfolded, but later, Abbey pulled me aside and quietly expressed concern. Apparently, Amber had shared stories of early childhood abuse, deeply personal and unsettling details that my aunt felt were both inappropriate for the occasion and indicative of deeper wounds.

“Choose your girlfriends more carefully,” she told me, her tone firm but not unkind. It was jarring advice—uninvited but not untrue. At the time, I didn’t know what to make of it. I was young, emotionally scattered, and still trying to piece together who I was as a sailor, a man, and a son in mourning.

That moment planted a seed—a lesson in boundaries, maturity, and the complexities of carrying other people’s pain when you're still trying to process your own. Amber and I didn’t last much longer after that, but the experience remains woven into my memory of that year. Part grief, part growth.

Life Beyond the Grinder

During those formative months at Machinist’s Mate A School and later Nuclear Power School, I forged bonds with shipmates who would accompany me through the crucible of nuclear training and the early days of my fleet career. Unlike boot camp, A School came with a luxury I hadn’t known in a while: free time. We weren’t completely cut loose, but I could finally explore a bit of Orlando’s nightlife and culture.

This was during Desert Storm, and America had suddenly rediscovered its appreciation for servicemembers. Uniforms turned heads. Military IDs opened doors. We weren’t treated with suspicion or indifference—we were seen, often quite literally, as heroes.

VIP at Universal Studios

One of the most surreal perks during this time was free VIP access to the newly opened Universal Studios Orlando. Just flash your military ID at the gate and in return you'd get unlimited access, front-of-the-line privileges, and even backstage entry to most attractions. For a broke, wide-eyed E-3, it felt like cheating—like you’d stumbled into some glitch in the simulation where you suddenly mattered.

Ironically, what I missed most about amusement parks were the lines. Not the wait—nobody likes that—but the opportunities. A 45-minute wait for Back to the Future meant 45 minutes of conversation with random, often beautiful, strangers. When you’re young, in shape, and wearing your "I'm in the military during a war" face, let’s just say the odds were better than even. But with VIP access, we skipped all that. Straight to the ride. No charm needed. And while that was cool, it wasn’t nearly as fun.

A Short Ride With a Blonde From King Kong

Still, one moment stands out. I was in a group of five shipmates when we got routed to the backstage entrance for the King Kong: Confrontation ride. We stood on the loading platform for a few minutes, waiting to board, when I noticed one of the Universal cast members—some mid-level guy—approaching me with a folded slip of paper. On it: a name and phone number, hastily scribbled. He mumbled, “The ride supervisor told me to give this to you.”

Looking up toward the elevated, glassed-in operator booth, I could just make out a blonde silhouette waving from behind the darkened glass. Apparently, I had made an impression.

That brief backstage glance turned into a two-week whirlwind romance—the kind that only exists in your early 20s, when time bends around hormones and possibility. We snuck in what visits we could, navigated the maze of pay phones and rigid duty schedules, but ultimately, like many things at that age, it faded.

Back then, there were no cell phones, no texting, no apps. You had one shot when you called the public pay phone in the barracks, and if someone else was using it—or ignoring your request to be summoned—you just lost that shot. And so, just like King Kong, the relationship roared briefly, climbed high, and then came tumbling down.

Chapter 25: Haze Gray and Underway

In October of 1992, I reported aboard the USS Baton Rouge (SSN 689), a Los Angeles-class fast attack submarine already steeped in notoriety. My assignment would stretch until my release from active duty in October 1994. At the time, the Baton Rouge still bore the scars—literal and symbolic—of its high-profile underwater collision with a Soviet submarine. We departed Norfolk, Virginia, bound for Mare Island Naval Shipyard in California on what would be her final voyage with a full crew. We ran at flank speed, no longer concerned with preserving the reactor core’s life—it was a one-way trip toward decommissioning.

The ship’s prior encounter with the Russian submarine K-276 Kostroma, during a covert surveillance operation off the coast of Severomorsk on February 11, 1992, cast a long shadow. Both subs were operating silently on passive sonar, blind to each other until the very last moment. The Kostroma, surfacing unexpectedly, struck the Baton Rouge near her stern. The impact crumpled her aft ballast tanks and left the Russian sub visibly gashed. By some miracle, there were no casualties, but the event carried consequences far beyond hull integrity. It fractured morale, and the aftershocks would ripple through the crew for months.

Following the incident, Commander JB Kolbeck assumed command. Though competent and by-the-book, his leadership was forced to contend with a ship’s crew denied the one thing that might have mended the rift: shore leave. Our long-anticipated liberty in Amsterdam—a well-earned chance for release and reconnection—was scrapped. In its place: more duty, more drills, and rising tension below decks.

Despite this, the crew powered forward. In drydock at Mare Island, we labored side by side with shipyard personnel to make the Baton Rouge whole again. Many of us pulled double shifts, taking pride in our resilience. But something had shifted. With morale low and little outlet for pressure, hazing rituals intensified, gradually twisting from rites of passage into more toxic forms of hierarchy enforcement. Tradition began to bend under strain.

Cranking in the Crawfish Inn

One of the most humbling yet unifying rituals aboard the Baton Rouge was Cranking—the Navy tradition where each enlisted sailor takes a temporary assignment as a Food Service Attendant. During my four-month tour in the galley, I learned firsthand what powered morale more than any motivational poster ever could: food. Our galley was affectionately dubbed the Crawfish Inn, and it wasn’t an ironic name.

Thanks to the submarine service’s inflated food budget, we operated more like a military-funded Golden Corral at sea—steak, lobster, French toast, and all-you-can-eat everything. The culinary spread was genuinely absurd for a warfighting machine submerged hundreds of feet beneath the ocean. It’s no surprise I gained 50 pounds in under a year, most of it while cranking. With physical activity options limited to a decrepit Stairmaster and a stationary bike that barely functioned, those extra meals stuck with me.

Equal Plates for All Ranks

Unlike surface ships, submarines don’t segregate the chow line. There’s one galley for everyone, and while officers dined in the Wardroom, they were still eating the exact same food—just plated and served for them. Our Food Service Chief, a former flag chef who had cooked for admirals, opted to bring his culinary talents underwater. His passion for cooking transformed our expectations of what military food could be.

I still remember the pizzeria-quality scratch-made pizzas, the steak dinners, and the time we served actual king crab legs. These meals weren’t just good for military food—they were good period. For once, a recruiter’s promise about "great Navy chow" wasn’t a lie.

Bucket Brigades and Submarine Storage Science

Getting underway for deployment wasn’t a simple matter of throwing pallets on board. It required a bucket brigade of sailors, shoulder to shoulder from the pier to the torpedo room, passing provisions hand to hand—hundreds of boxes, crates, and cans. There’s no loading dock on a submarine; the entire crew became logistics.

Every inch of space aboard the Baton Rouge was precious. We packed stores into every available cavity, from overheads to bilges. Some passageways were so crammed with goods that I had to duck walk just to get through them. It was a lesson in both efficiency and humility—serving meals I helped carry aboard in spaces barely wide enough to turn around in.

Friday Morning Launches: The Nuclear Wake-Up Call

During my operational year aboard the USS Baton Rouge, a rhythm developed that came to define our weeks: we left almost every Friday morning. If you were in the transit duty section, this meant showing up at 0330 sharp. As nuclear-trained personnel, our startup ritual was an intricate ballet of valves, checklists, and reactor plant procedures, culminating by about 0730 with the reactor fully heated up and ready to go.

By contrast, the “Coners”—non-nuclear personnel who occupied the forward sections of the sub—had a far simpler task. Their system startup usually involved something like flipping a switch and waiting. This contrast fueled an ongoing and deep-rooted rivalry between the nukes and the non-nukes, and between A-Gangers (conventional machinist's mates) and nuclear MMs. The jokes never ended. One that stuck with me:

"Coners get the [bleep] and nukes get the shaft."

We took it as a badge of honor.

The Irony of "Haze Gray and Underway"

I often chuckled at the not-so-empty threats made by instructors during A School, Power School, and Prototype:

“If you fail out, you’ll be haze gray and underway chipping paint.”

Well, spoiler alert: I graduated. I didn’t fail out. And yet, I still found myself haze gray, underway, and chipping a whole lot of paint.

My daily routine as a crank (Food Service Attendant) often included three to four hours of brightwork polishing in the midships passageway. It was a ritual that demanded patience, precision, and an odd sense of pride. The Navy doesn’t just want you to run a reactor—they want the stainless steel rails and trim to be so polished they can reflect your soul.

Master of the TDU Tube Turds

The real education came in the Trash Disposal Unit (TDU) room, where I developed a skill that no textbook ever covered. This was the dirty business of compacting the day’s waste into “TDU tube turds.” These compacted metal tubes were hand-assembled from flat stamped steel sheets, origami-folded into tubes with tabs that had to be bent down precisely. You'd drop in a weight, load it into the hydraulic compactor, and pull the lever—watching putrid, fermented goo ooze through the vent holes. That slime had a stench so potent it would cling to your skin, uniform, and very soul.

I routinely spent 12 to 14 hours per day in that sealed metal room, wading through the rotting waste of 140 sailors, building and loading those damn tubes, sealing them, and sending them off to their deep-sea graves. The smell was so bad it turned me into a walking biohazard, earning me a wide berth from the rest of the crew no matter where I went.

TDU Day: The Trash Ceremony of the Deep

TDU Day aboard the USS Baton Rouge wasn’t just about waste disposal—it was practically a ceremonial affair. After rising to periscope depth, a coner chief would descend to the TDU room to supervise the ritual. Communication was routed through sound-powered phones, and once we had a solid link with control, we’d begin the sequence.

With eight or nine “TDU tube turds”—those carefully folded metal containers filled with compacted shipboard waste—loaded up like refuse torpedoes, the launch began. Each tube was dropped into the loading tray, sealed tight, and ejected into the ocean one by one with methodical, almost reverent coordination.

As strange as it sounds, this was one of the few moments in the trash detail that actually felt satisfying. It turned the drudgery of compacting garbage in a stinking hot box into something resembling a climactic release, both figuratively and literally. There’s a weird kind of pride in knowing you’ve launched something into the abyss.

A Submarine’s Early Death: Clinton’s Cuts & Baton Rouge’s Fate

When I first checked aboard the Baton Rouge, the plan was to refuel the ship during my second year. Given the expected 30+ years of service life post-refueling for a 688-class fast attack sub, this seemed like standard ops.

But politics got in the way.

In the wake of the Soviet sub collision, and with President Clinton’s campaign promises to cut defense spending, our boat was selected as the first 688-class sub to be decommissioned early. A rumor persisted among the crew—maybe half myth, maybe half-truth—that Baton Rouge was originally designated SSN 688. But due to delays in construction or scheduling mishaps, it was rebranded as SSN 689, and USS Los Angeles took the inaugural 688 hull number. That tidbit, if true, only added to the ship’s mystique and sting of early retirement.

Tight Bonds and Near Bar Fights in Puerto Rico

Despite the politics and the smell of TDU juice, service aboard the Baton Rouge forged strong bonds. I had several close shipmates: Andrew Jones, Kenneth Senn, and Louis Deleandro, to name a few. But one particular memory stands out.

While we were docked at Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico, on a low-key weeknight shore leave, five of us ventured to the only open bar outside base. The place was empty except for us—until five Marines walked in.

Now, if you know Marines and you know sailors, you know where this could’ve gone. These guys weren’t there to swap stories or buy us a round. They wanted to fight. And although I was the biggest in our group at 6’1”, 230 lbs, these Marines still had size, strength, and the home field advantage.

But then came Petty Officer First Class Steven Denoia. He was the head of the Electrician’s Division and, as it turned out, a master of verbal judo. With the smoothness that would later land him success in the business world, Denoia disarmed the whole situation with a few well-timed jokes and genuine friendliness. What could’ve been a full-blown brawl turned into drinks, laughter, and even a few exchanged stories. Classic military life—tense one second, unforgettable the next.

The Accidental Gift of Decommissioning

As fate would have it, being assigned to the first 688-class submarine to be decommissioned turned out to be an unexpected blessing. Because there was no formal playbook for our class, a significant part of our mission became writing the procedures ourselves.

For earlier submarines, the decommissioning process had been tightened to a 3–4 month evolution, but for us, it unfolded more like an extended, lightly-supervised sabbatical at Mare Island Naval Shipyard. The pace was slower, the expectations fuzzier, and the days—while still filled with work—left room for things like personal development, exploration, and actual rest, a luxury rarely found in submarine service.

Cross-Country Orders: A Geo Storm and $600 Freedom

And then came the cherry on top.

As a Geo Storm GSI owner and a sailor receiving a Permanent Change of Duty Station (PCS), I was given a modest but mighty $600 travel stipend and a free pass to drive across the country from Norfolk, Virginia, to Mare Island, California.

This was more than just a relocation—it was a rite of passage. A solo journey across the American continent, in a car I’d customized and loved, represented a brief chapter of true freedom. For once, the military had handed me an opportunity that didn’t come with barking commands or shipboard confinement. It came with open roads, gas stations, roadside diners, and a stereo system tuned to the soundtrack of my life.

And it was perfect.

The Thrill Kill Cult Rides Again

Life at Mare Island wasn’t all procedural manuals and shipyard monotony. In fact, it might've been the closest the Navy ever got to issuing me a vacation. Enter the Thrill Kill Cult—not the band, but our crew: Ken Senn, Andy Jones, Lou Deleandro, and yours truly. Together, we turned Northern California into our personal playground.

From bar-hopping in Napa Valley to aimless drives through the redwoods and coastal fog, we lived like we were invincible. Four freshly-cut sailors stuffed into my red Geo Storm GSI, stereo thumping, freedom echoing off the canyon walls—it was peak early-90s outlaw Americana.

Golden Gate Tollgate Mayhem

One of our more, let’s say, creative maneuvers happened near the Golden Gate Bridge. With zero foresight and exactly no toll money, I made the executive decision to reverse off the on-ramp like it was a Grand Theft Auto mission.

Enter: Sergeant Reno 911—a California highway patrol officer with sunglasses too small for his mustache and enough sass for a sitcom. The ticket he wrote? Never paid. Add it to the growing list of bad ideas that somehow made life more memorable.

Sacramento: More Tickets, More Laughs

Just in case our record needed padding, Sacramento came through. An illegal U-turn later, we were yet again explaining ourselves to a confused cop while trying not to laugh. We never did figure out why the U-turn was illegal—chalk it up to military logic clashing with civilian infrastructure.

But that was the nature of the Mare Island interlude: a cocktail of youth, horsepower, and just enough recklessness to make every week a story worth retelling.

Wiser (Maybe), Grateful (Definitely)

Through it all, I gained more than fines and stories. I forged lifelong friendships, experienced California’s soul, and learned a few hard-earned lessons—like maybe don’t reverse off major toll bridges, and always check local traffic laws before trusting your gut.

But mostly? I’m just grateful.

Grateful for those guys, that car, that time, and everything it taught me about loyalty, freedom, and how far a full tank and a good stereo can take you.

The Prototype Years and the Pull of the Road

Five-Day Weekends and the Call of Dave

Throughout my time at Nuclear Prototype School in Ballston Spa, NY, and later while stationed aboard the USS Baton Rouge in Norfolk, I developed a survival ritual: driving to see Dave Laime. Those "five-day weekends" (which sometimes stretched a little longer than scheduled) were a lifeline. No matter how grueling the week—whether it was heat stress drills in Ballston Spa or bilge-cleaning rotations in Norfolk—I knew that if I could just get to Northern Virginia, Dave would be there, and with him, a guaranteed good time.

And Dave wasn’t just anyone. He was a force—funny, charismatic, musically brilliant, and the gravitational center of whatever orbit he entered. As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, entire volumes could be written just chronicling the adventures we shared, and still, they wouldn’t do justice to his impact on my life.

The Naked Soul Brotherhood

During this era, Dave was fronting a band called the Naked Soul Brothers, playing small venues across Northern Virginia with a motley crew of deeply talented musicians. Every visit home followed a pattern: hug Barbara, his amazing and eternally welcoming mom; descend into the finished basement, Dave’s personal headquarters; and map out the weekend’s conquests, both musical and social.

There were always house parties, always gigs, and always groupies—lots and lots of groupies. And when your best friend has the kind of charm that pulls in women like gravity itself, let’s just say being the wingman was an amazing position to be in. He could only entertain one (maybe two), so there were always opportunities for me, the self-proclaimed "scrub hangin’ out the passenger side."

Zero regrets. Those nights were unforgettable.

Westbound Cannonball: From Dulles to Topeka

When orders came through for the Baton Rouge to head west for decommissioning, I turned it into the ultimate solo road trip.

The first stop was obvious: Dave’s house. One last hug for Barbara. One last weekend of Rehoboth flashbacks and basement band plans. Then, in the quiet of the evening, I loaded up the Geo Storm GSI, queued up my best mix tapes, and pointed west.

From Dulles to Topeka, I drove nonstop—36 hours straight. No stimulants beyond what was legally available in gas stations: Vivarin tablets, ephedrine, and the raw inertia of youth and momentum. It was my own personal Cannonball Run, and I was hell-bent on making time.

Looking back, I don’t know if I was running toward something or just refusing to slow down. Probably both. But I do know this: the first leg of that trip, powered by nostalgia, caffeine, and the ghost of the weekend I’d just had with Dave, felt like the purest kind of freedom.

Chapter 26: Cross-Country Freedom and Salt-Soaked Speed

Topeka: Temptation and a Gentle Letdown

Topeka was where the road started to feel like a real sailor’s journey—wild, indulgent, and just a little reckless. Late that night, I did what only sailors seem to do: I found a gentleman's club. One hundred bucks and a handful of bold tips later, I found myself invited back to a hotel room by the dancer I’d been eyeing. I paid for the room, the anticipation was thick… and then, she fell asleep. Dead to the world. Totally unrequited. Honestly, it was probably for the best.

Boulder: Ghosts of Girls and Familiar Malls

From there, I set my sights on Boulder, Colorado, where Precious—yes, that was really her name—a girl I had dated briefly during one of my visits with Dave, was enrolled. Despite my best efforts and a full day spent exploring the town and a shopping center that felt exactly like Lake Forest Mall back in Gaithersburg, Maryland, we never did reconnect. No cell phones. No DMs. Just hopes—and a lot of unreturned calls to dorm landlines. Still, I carry a fond memory of that day, the unfamiliar streets, and the warmth of possibility that never quite materialized.

Utah Awakening: Beauty in the Quiet Hours

Crossing into Utah, I remember pulling over to sleep on an on-ramp sometime in the early morning hours. When I woke up, it was to one of the most breathtaking sunrises I had ever seen—vast, open desert terrain painted in hues I wasn’t used to growing up on the East Coast. The light felt clean. Honest. Like I had driven off the edge of the map and into a better version of reality.

Salt Fever: Bonneville at 124 MPH

Then came the Bonneville Salt Flats—a pilgrimage site for anyone even remotely obsessed with speed records. As a kid, I had devoured every story about the Blue Flame, the Budweiser Rocket Car, and the legends who raced across this otherworldly surface. The access road stretched into the white abyss, and I couldn't help myself. I pinned the pedal of my Geo Storm GSI to the floor, redlined all the way, chasing dreams and trying to punch through the sky. I hit 124 mph, drag-limited, but triumphant nonetheless. I stopped short of the actual lakebed—the salt was soft and wet—but the moment? Pure velocity. Pure joy.

Tahoe, Serendipity, and the $5 Tortellini

Not long after, I saw a sign for Lake Tahoe, and something just pulled me toward it. No GPS back then—just my tattered Rand McNally Atlas with scribbles and coffee stains guiding me west. Around 9:00 PM on a Friday night, I was winding along a two-lane road when I saw two attractive girls walking in the moonlight.

Naturally, I stopped. They said they were headed to a bonfire and asked if I wanted to join. Did I ever.

We pulled up to a clearing on a hill lit by fire and filled with locals—maybe a hundred people, laughter echoing under a dusty, moonlit sky. It felt timeless. When the bonfire wrapped, they looked at me and said, "The best meal in this part of the country? A casino in Reno."

So we went. They weren’t lying—tortellini alla fini with mushroom sauce, absolutely drowning in creamy perfection, for $5.00. Even then, that was a steal. I treated both of them, shared a few stories, and eventually dropped them off. No numbers exchanged, no promises made. Just a night of dust, firelight, and pasta.

And then, back to the road. Still headed west. Still smiling.

Chapter 27: Vallejo, Angles and Dangles, and Full Steam Ahead

First Impressions of Vallejo and a Hidden Geo Storm

From Reno, I raced down through central California, tasting a brand-new kind of freedom. Everything felt different. The humidity—or lack thereof—was a revelation. Your sweat actually worked. It evaporated, leaving you cool and comfortable instead of sticky and miserable. For a guy raised in the swampy air of the East Coast, this was nothing short of revolutionary.

I arrived in Vallejo, and it was like stepping into another planet—my first Jack in the Box and a completely foreign landscape of WWII-era bunkers, dry heat, and gritty industrial charm. I parked my beloved Geo Storm GSI in one of the old concrete naval bunkers along the Mare Island shoreline, where it would sit until I flew back to Norfolk for the boat transit. It felt like I was stashing a part of myself for safekeeping.

Family on Board: Angles and Dangles

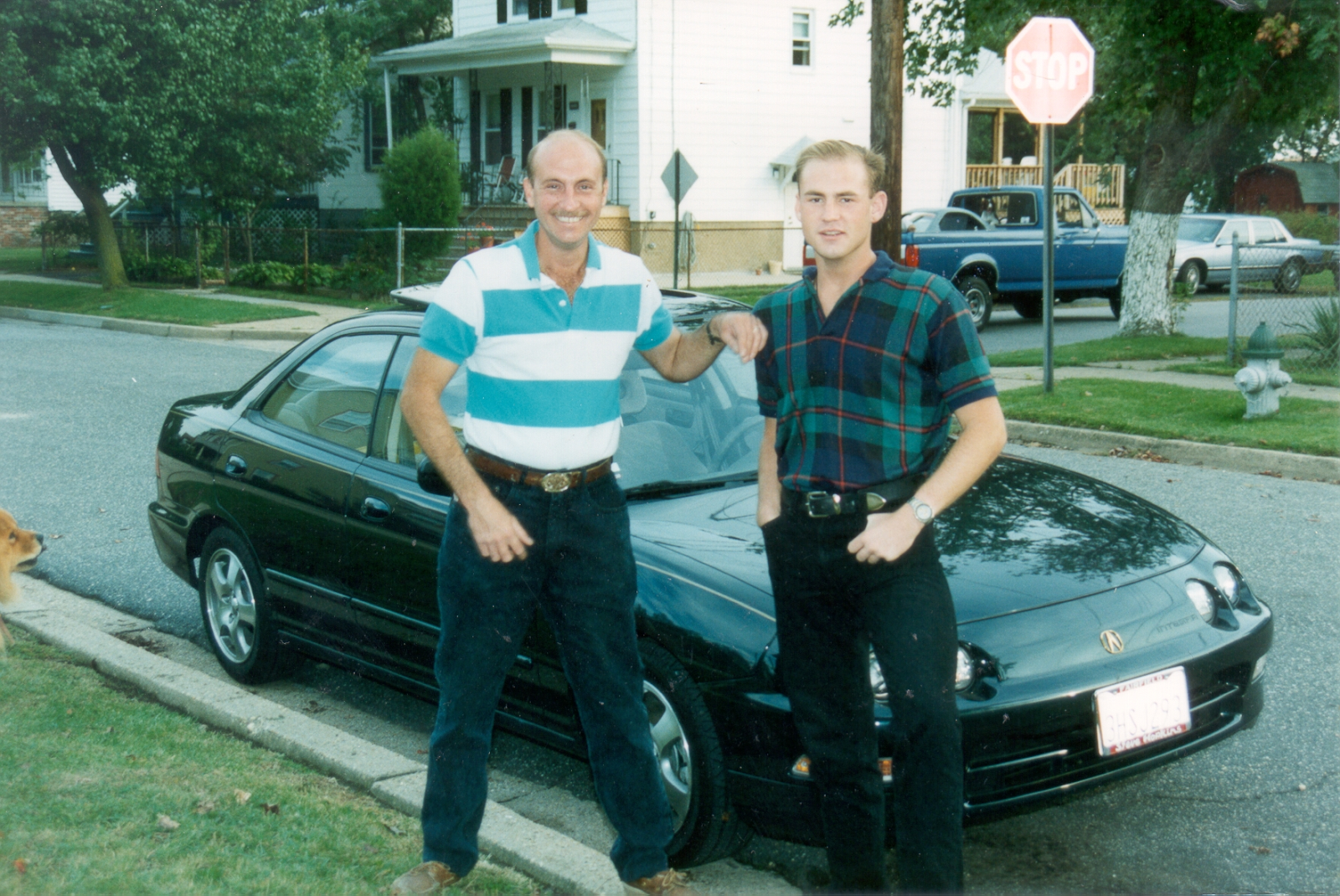

While I was making my way west, the USS Baton Rouge held a dependents' cruise, a special event where family members are invited aboard for a taste of submarine life. Both my father and brother joined, and it was one of those rare full-circle moments—family stepping into the world I had immersed myself in.

They were awestruck by the "Angles and Dangles" exercise, where the boat performs dramatic maneuvers, including an emergency blow that sends the sub rocketing upward at steep inclines. For once, they didn’t just hear about it—they felt it. It gave them a visceral appreciation of what submarine service really meant, and gave me pride in showing them what I did for a living.

Final Goodbyes and Full Flank to Mare Island

Back in Norfolk, it was time to wrap things up. I packed the rest of my meager belongings, said goodbye to my few remaining connections, and reported for the boat’s final cruise. This wasn’t your standard crawl-speed transit either. We were hauling ass.

Because the Baton Rouge still had significant reactor life left, we didn’t need to baby the core like most submarines on their final legs. We were flank speed through the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific—and you could feel it. Most times, subs glide silently, so smooth you barely remember you're underway. Not this time. The rhythmic oscillation of the hull, the steady hum of speed slicing through the sea—you were reminded constantly that you were aboard a war machine with somewhere to be.

Photo Caption: Ken Standing on deck of USS Baton Rouge, SSN 689 Oct 1, 1993 1:21 PM

Victoria, British Columbia: A Week of Solace

One of the hidden gifts of the journey came when we stopped in Victoria, BC for what turned into an unexpected week of liberty. Still tinged with the sting of our cancelled Amsterdam port call the previous year, this stop brought needed balance.

Victoria was a gorgeous fusion of British influence and Pacific Coast chill. We wandered cobblestone-like alleys, sampled the local ales, mingled with friendly Canadians, and—most importantly—reconnected as a crew. You could argue that port calls were the Navy’s best team-building exercise, and Victoria proved that tenfold.

Sailors Forged in Steel

As we crept closer to Mare Island, the Baton Rouge began its final approach. There was an odd electricity in the air—equal parts relief, reflection, and anticipation. For many of us, this was the end of an era.

There were still drills. Still long hours. Still the constant readiness that submarine life demanded. But there was also a deepening camaraderie—a bond formed in steel, pressure, and shared hardship.

This journey wasn’t just about a vessel being decommissioned. It was about a crew navigating their own transitions—young men becoming leaders, shipmates becoming brothers, and lives being shaped one dive, one watch, one TDU tube at a time.

Deactivation: Less Systems, More Freedom

As the deactivation of the USS Baton Rouge progressed, a fascinating and fortuitous pattern began to emerge. Each system we shut down translated to one less maintenance burden—a direct and tangible improvement to our daily lives.

This shift in pace wasn’t just technical—it was liberating. We had fewer drills. Less midnight oil to burn. The ship began to quiet. As each pump, valve, or generator was tagged out and powered down, we inched closer to a sailor’s dream: liberty.

The Spare Parts Nightmare

Before all that, though, we lived through what I now consider one of the most galling inefficiencies of submarine life: the Navy spare parts system.

While we were still stationed in Norfolk, another sub in Submarine Squadron 8 urgently needed a 10K distiller lower-pressure brine pump. As fate would have it, that pump was identical in every way—form, fit, function—to our auxiliary seawater pumps. Same manufacturer. Same model. Same size. Same mounts. Identical. Except, of course, for one minor and profoundly Navy-specific detail: the part number was different.

And so, the Navy being the Navy, there was no chance of just swapping out the easily accessible seawater pump. Instead, we had to fully tag out the 10K distiller system, drain and isolate it, and disassemble a maze of piping and cabling to surgically extract the pump from deep inside the unit. Only then could we hand the pump over to the sub that was preparing to get underway.

After that, we waited on a new pump, reversed the whole process, and spent days putting the system back together again.

This kind of senseless logistical red tape was how our “non-duty” days routinely stretched from 0730 to 1930, and duty days turned into 20-hour grinds. It was just one of the many realities that made life in Machinist’s Mate division an often brutal exercise in perseverance.

Shutdown Schedules and Four-Section Liberty

But as we got further into the deactivation process, things started to shift.

With each system that went offline, our lives got a little lighter. Our days now began with an 0830 muster, followed by a few hours of light training or task work. By 1130, we were typically released—liberty granted for the rest of the day.

With the ship no longer in an operational cycle, we adopted a four-section duty rotation. This meant every fourth night, I would stand Shutdown Rover Watch—patrolling the now-defueled and dormant submarine during the silent overnight hours.

Rover Watch: Alone on a War Machine

Those nights left a deep impression on me. There was something hauntingly beautiful about walking the full length of the Baton Rouge alone. With every echo of my boots down the passageways, I was reminded of what the ship once was—a billion-dollar nuclear-powered war machine, now resting in slumber.

It was eerie. And solemn. And yet… I loved it.

There was a profound sense of pride in being the only living soul aboard, entrusted with guarding this technological leviathan while the world outside went on sleeping.

Perspective from the Dry Dock

Whether standing rover, glancing up at the hull from dry dock, or walking down the gangway into a Caribbean port, I always carried a heavy but welcome pride.

To emerge from that stealthy hull into the light, seeing the stares of onlookers—some filled with curiosity, others with awe—made it clear: this wasn’t just a job. This was a calling, even if it meant oozing TDUs, endless brightwork, or archaic parts catalogs.

Every painful maintenance task. Every missed port call. Every long day. It was part of something bigger. And even in the quiet days of shutdown, you still felt it.

Chapter 28: The Horse and Cow, Part I — Relics, Revelry, and the Woman Who Changed My Life

A Bar Steeped in Submarine Lore

It was shortly after arriving at Mare Island that I met the woman who would eventually become my wife, Anita. The scene of this pivotal moment? A place that could only exist in a town like Vallejo—a town with salt in its bones and submarines in its soul. That place was the Horse and Cow.

More than just a bar, the Horse and Cow was a cathedral to submarine culture. Walk through its doors and you weren’t stepping into a dive—you were stepping into a museum. Every inch of wall space, ceiling tile, and support beam was plastered with naval memorabilia: ship plaques, belt buckles, toilet seats from decommissioned boats, photos from tours long past, challenge coins, and even full-sized rigging pieces. It was all there, honoring the legacy of submariners past and present, especially those connected to the Mare Island Naval Shipyard.

The Float and the Flavor

The centerpiece—both absurd and majestic—was a roughly 40-foot-long parade float modeled after a submarine, resting casually next to the dance floor like a sleeping giant. The bar thrummed with a soundtrack that jumped between country hits, '90s rock, and the occasional synth-beat club track. In one corner, pool balls cracked with mechanical regularity. In another, barstools creaked as lifers, lovers, and lost souls nursed cheap drinks and swapped sea stories.

It had a scent—beer, bleach, brass polish, and nostalgia—and that scent is burned into memory.

Meeting Anita

It was on one of those random, nothing-special nights that fate flipped a coin.

I was out with my roommate Bud Thompson, a guy who'd been my ride-or-die through many a hazy evening. We bellied up to the bar like we had a hundred times before. And there she was—Anita, working the room like she owned it without even trying. She wasn’t flashy; she was magnetic. Older than me, confident, stylish, and with a look in her eye like she’d seen a few things but hadn’t let the world break her. We locked eyes, shared a laugh, and before the night was over, I knew I’d met someone different.

We talked. We danced. We shared stories. And somewhere between the jukebox and that parade float, something real began.

The Night That Changed It All

The Horse and Cow wasn’t just the place I met Anita—it was also the scene of a cautionary tale wrapped in liquor and blurred intentions. One night, after more drinks than I should’ve had, I got caught up in a bizarre situation involving a girl and her friend—one of those experiences you laugh about later, but also one that slaps a little truth into you.

It was that night I made a decision: no more drinking. Not for a while, anyway. The clarity that came the morning after changed the trajectory of my life. It was a silly little misfire in the moment, but it planted a seed—that maybe it was time to grow up a bit.

Funny how those moments work. You're not planning them. You’re not looking for them. But they show up, drunk and dressed in irony, and they shape your future.

The Horse and Cow? Yeah, it was just a bar. But it was also the first domino in a line of profound personal milestones—a bar that served more than just drinks. It served turning points.

Chapter 28: The Horse and Cow, Part II — The Fight Before the Farewell

The Missed Shot and the One That Landed

Before I dive into the early days of my courtship with Anita, I’ve got to recount one of the more momentous and unexpected fights of my life, and it happened right where so many stories of my Navy years found their stage: the Horse and Cow.

I was there, as I often was in those final days before leaving Mare Island, with one simple goal: muster the courage to ask out Yoli, the beautiful, sharp-witted bartender who’d caught my eye from day one. She was older, confident, always composed—and in another one of life’s predictable ironies, when I finally worked up the nerve to ask her out, she said yes.

But I was heading out. My time at Mare Island was nearing its end, and with it, that door closed too. Just another missed opportunity to stack onto the long list we all carry—the ones that got away.

The Accusation

That night, I wasn’t drinking. I had given up alcohol earlier that year—a personal choice born from too many nights where bad decisions came free with every third beer. I was sipping ice water behind the bar, playing pool, listening to music, and feeling the strange weight of imminent transition.

Three sailors were next to me, doing what sailors do: playing pool, drinking, running their mouths. One of them gave me a strange look. “Did you dye your hair before?” he asked. “Didn’t you used to be heavier?” I laughed it off. I’d lost a lot of weight, dyed my hair black for a stretch, and yeah—I looked different. “That’s me,” I replied. “Put in the work, dropped some pounds.”

Then came the punchline—or the gut-punch.

“You were hitting on my wife.”

The Fight

His tone wasn’t playful, and now the tension was thick. I looked at him, somewhere between confused and disbelieving. I tried to deescalate, saying, “C’mon man, no harm, no foul. Just talking. It’s all fun and games.”

What I should’ve said was something like: “You brought your wife to the Horse and Cow? Seriously? What’d you expect?” But I didn’t. I kept it cool. Or tried to.

The slap he aimed at me was weak—a flailing move, not a punch. Instinct took over. I shot in and grappled him to the floor. Years of high school wrestling and wax-on-wax-off dojo drills kicked in. I had him grounded, and started landing some blows, but I’d overlooked one thing: his two shipmates.

Suddenly, boots were slamming into my side and back, the two of them piling on while I was still entangled with their buddy. I managed to twist out, got to my feet, and limped off with just a bruised ankle—but it was a fight I hadn’t asked for, and one I wasn’t going to back down from.

The Aftermath

The next morning, I passed out in the shower.

The pain from the ankle swelled into something deeper—a dull, all-consuming ache—and I collapsed, naked and alone, in the stall. I came to, soaked and stunned, and hobbled back to my room before heading to medical.

Of course, medical didn’t see a three-on-one assault. They saw a sailor in a fight. I got a reprimand—one that would shadow me later, when newly frocked Ken Whitson decided to make an example of me for what was, by any sane standard, a minor infraction.

But I never tried to lie or make excuses. I didn’t throw the first punch—or the first slap, for that matter. I stood my ground. And sometimes? Sometimes you just have to fight.

Chapter 28: The Horse and Cow, Part III — The Girl, the Roommate, and the Dart

The Encounter

As it happened, the story of how I met Anita, my future wife, is... well, a little embarrassing. But it’s part of the tapestry, and to leave it out would be dishonest.

It was a typical night at the Horse and Cow, that shrine to submariners and ill-advised choices. My roommate Bud Thompson and I had already logged many hours there, soaking in the atmosphere, the history, and the cheap drinks. That night, Anita stood out. She was with a townie—nothing special about him—but she? She was elfin, tiny at just 4'11", and strikingly beautiful in a way that was both delicate and magnetic.

I was too shy to say a word. Bud wasn’t. He went for it, struck up a conversation, and came back with her number.

Then he disappeared.

For a week.

When he returned to our room, he looked defeated—holding a container of home-cooked food Anita had made for him. “That girl is crazy,” he said, “I've known her a week and she's already cooking for me and telling me she loves me!” He was done.

I thought, That sounds great, and without hesitation, I asked for her number.

January 15th, 1994

Our first date was my birthday—January 15th. We hit some rock bar, tagging along with her friend Tirena, who was infatuated with a guy in the band. I don’t remember the music, but I remember the way everything clicked. Later that night, after dropping off Tirena, Anita and I ended up back at her apartment in Vallejo.

Cue the universal law of unintended consequences:

“Be careful what you wish for—you might just get it.”

The Dodge Dart and the Invisible Husband

Anita lived right off base. The apartment complex had a pool, hot tub, and a seriously nostalgic Dodge Dart parked outside. I found it charming—until I found out it belonged to her current husband.

The backstory was straight out of a military soap opera. Her husband, a former A-Ganger aboard the Kamiah Maiah (a converted special ops boomer), had taken geo-bachelor orders to Hawaii. Anita stayed behind. Her excuse? She “needed to be close for her grandmother’s funeral.” The kicker? Both grandmothers were still alive, well into their 80s.

That should’ve been a red flag. But love—and lust—makes fools of us all.

Boot Camp Proposals and Other Bad Ideas

To be fair, her husband didn’t have a prayer. He met her through a mutual friend during their first boot camp leave in Chillicothe, and within a week, he proposed. Because, why not? You meet a girl on leave, you're 18 and infatuated—it seemed like the thing to do.

I've done a lot of reflection since then. I don’t say any of this to mock him. He was probably a decent guy—just in way over his head. I have since tried to live by an ethos of minimizing harm. That relationship, from where I stood, was already over, even if the paperwork said otherwise.

I wish him peace. I really do.

Bud, The Fallout, and the Healing

As for Bud—our friendship didn't survive unscathed. I was smug, I won’t lie. I didn’t hide my happiness with Anita. In fact, I rubbed it in. While he stewed in the aftermath of their brief crash-and-burn, I basked in my newfound relationship. I got cocky. And I know it hurt him.

Years later, just before I went in, Bud and I reconnected. We had a long, cathartic talk. He apologized for what had happened in the shipyard. I apologized too—for the things I said and did that rubbed salt in those wounds. That conversation brought me a lot of peace.

I’d carried some of those wounds for a long time. He had too. Funny how two guys in their early twenties, caught in the throes of rivalry, booze, and heartbreak, could do that much damage. But healing’s real, and I’m grateful we had the chance to set things right.

Chapter 29: Exit Strategy — Anita, Skates, and the Shape of Things

Pilot Wings, Vallejo Eats, and the Honeymoon Phase

In the beginning, my time with Anita was genuinely enjoyable. We’d hit restaurants around Vallejo, but mostly, we did what sailors do best—practice. In the quiet hours, we’d log countless missions on Pilot Wings 64, burning hours on her Nintendo 64 while the rest of the world faded into background noise. For a while, it felt like a groove. A rhythm.

The Break

But rhythms fade. Over time, my growing unease with the relationship started to surface. I had the Navy, and the base, and the daily grind of duty to hide behind. That shield gave me enough distance to break it off. She kept tabs, sure—through her friendships with my shipmates—but I was able to cut ties cleanly. No hard feelings. No explosions. Just a silent fade to black.

Several months later, she moved to San Diego, where her husband, still active-duty, got a permanent change of duty station. One weekend, I made the drive down to see her. We met at the Denny’s across the street from where she was staying. And when I saw her—it was like that scene from The Mask:

"Our love is like a red, red rose, and I am a little thorny."

Before me stood a miniature Daisy Duke, dimensionally flawless, radiating like a walking punchline to all my best efforts at discipline. What was I to do?

Body Image and the War Within

At the same time, I was waging a completely different war—a private one.

I’ve said it before: I’ve battled weight my entire life. But during our ship’s stay at Mare Island Naval Shipyard, I crossed a threshold. I developed an anorexia-adjacent obsession with weight loss. I was working out four to six hours a day and eating next to nothing.

From my peak of 240 pounds at the beginning of drydock, I dropped to 165 pounds by the time I exited the Navy in September 1994.

This wasn’t just about looks. This was about control. About fighting for mastery over something in my life. And weirdly enough, it came with some benefits.

Raves, Ice Rinks, and 5 AM Muster

I dedicated Sundays and Mondays to skating—no matter what. I became a regular at the Berkeley Ice Arena, particularly for the adult sessions. That’s where I met a girl who taught lessons, and we became fast platonic friends. She introduced me to a scene I hadn’t seen before—house parties, late-night raves, and underground clubs.

Thanks to the odd schedules at Mare Island, I could make it work. We'd be out until 5:00 AM, I’d power through muster, then crash for four or five hours before getting up and doing it all over again. Skating, raving, and starving—an unlikely but strangely liberating combo that defined the final months of my Navy career.

Chapter 30: Skating Valleys, Losing Grip

The Contra Costa Canal Trail — Pure Freedom on Wheels

During my final year in the Navy, one of the most grounding experiences was discovering the Contra Costa Canal Trail network. It stretched for hundreds of miles, winding through valleys, beside concrete canals, under sun-soaked skies. The smooth pavement and scenic views made it a skater’s paradise. I spent countless hours on my inline skates, carving through suburban beauty and pastoral stillness. It was meditation in motion.

Diverse Company, Clear Identity

Around this time, I built a pretty eclectic friend group. While there wasn’t much ethnic diversity, there was a broad spectrum of sexual identities. For clarity’s sake—and with no offense meant—I’ll say again: I’m 100% heterosexual. I’ve always been wired to love the female form. Still, I found these friendships fulfilling, and I admired the authenticity many of them had in living out who they were.

The Girl from Novato — Almost Something More

In this whirlwind of transformation, I met a girl who stood out. Her family was fabulously wealthy, living on a mountaintop in Novato. It felt like something out of a John Hughes script—rich girl, Navy guy, different worlds colliding. I messed it up, of course. But even after we drifted apart, we reconnected years later when she became a cruise director for Norwegian Cruise Lines. We shared a week-long tryst. Like many chapters in my love life, it ended with no hard feelings, but no lasting connection either. Still—what an adventure.

Victim Stance and the Chip on My Shoulder

The truth is, I wasn’t in a great headspace. RMA had instilled in me a kind of conceit, a sense that I was better than the life I found as an enlisted man. I carried that chip into every interaction. On the surface, I was respectful—"yes sir," "no sir"—but my tone was brittle. My attitude gave me away.

If I were to do it all over again, I think they’d feel the difference. Real respect. True humility. But back then, I was angry and insecure, constantly feeling my stomach to check whether the fat had returned. I had this weird tic—smelling my wrist—something that probably came off even stranger than it was.

Bud and the Norfolk Reunion — The Dark Turn

Things got worse at home. Bud, my once-friend and roommate, turned on me. He’d teamed up with my former Norfolk roommate—his new best friend—and together they made it their mission to break me. One night, they destroyed the bicycle assigned to me by the shipyard, leaving it twisted in front of the barge like some middle school mafia hit. It wasn’t subtle. It was cruel, and it broke something inside me.

Midwatch and the Breaking Point

In my watch section, E5 James Woods, an Engineering Laboratory Technician Machinist's Mate, kept showing up late to relieve me. Every single duty day, the guy would sleep in later and later while I covered the gap. There was an unspoken rule: Don’t rat. Don’t tell. He leaned on that, hard.

Then, one day, he just didn’t show up at all. Slept through an entire midwatch.

Me? I said nothing. But I was boiling over.

Chapter 31: The Beginning of the End

The Retaliation That Backfired

The next duty day, fed up and quietly seething, I made a conscious decision to be ten minutes late relieving ELT James Woods. I figured it was fair—he’d been late constantly, and I’d been the good soldier every time. But he wasn’t one to let it go. He reported me to his section chief, which wasn’t even in my chain of command. That complaint triggered a confrontation between us, an argument loud enough to be overheard by our newly frocked-to-Chief but still technically an E6, Kenneth Whitson.

Meet the "Diggit"

Whitson was a classic Navy archetype—a “Diggit.” The guy ate, breathed, and slept the Navy, and we resented him for it. He always showed up early. He never left on time. He’d post up in the barge office with his feet on a desk, whistling like a lunatic and accomplishing nothing, 12 hours a day. While the rest of us counted the days, he made the Navy his entire identity.

But now he had a new stripe—a Chief’s anchor freshly frocked to his collar. He was eager to prove something, and unfortunately, I was the one who gave him an excuse.

The Missed Meeting

After overhearing the argument, Whitson told both Woods and me to meet him on the barge after muster the next morning. But the following morning, I was still in my routine. After a duty day, you typically got to hit the trail after morning muster. That’s what I did—completely forgetting the meeting. It wasn’t defiance. It was just muscle memory.

When I came back aboard later, everyone knew. The whispers were all around the barge—Whitson was on a warpath. I heard that he’d filed charges against me.

Article 92 — Wait, What?

Charges? That word hit me like a torpedo.

Shortly after, it was made official: Article 92 — Failure to Follow a Lawful Order. I was stunned. No counsel. No briefing. No warning. Just paperwork and procedure. Suddenly I was facing serious military punishment for what felt like a non-event.

Here I was—a guy who had kept his mouth shut through months of hazing, missed watches, and outright sabotage. I had taken it all on the chin, trying to finish my time with as much honor and dignity as I could muster. And now, this?

I was confused, angry, and—more than anything—I felt betrayed.

Chapter 32: Captain’s Mast and the Fallout

The Decision to Face the Music

So—ignorantly, naively—I chose to go to Captain's Mast.

I thought, Hey, I spent all that time with Commander Kolbeck on the ORSE inspection team. He knows me. He knows my work ethic. Surely, he’ll hear me out. What’s the worst that could happen?

I pressed my uniform to perfection, marched into his office on the barge, and sat down across from the man who once greeted me with familiarity and respect. I told him my side of the story—calm, composed, honest. And when I finished?

He demoted me.

Just like that. No sympathy. No discussion. Just a drop to E3 and a vague punishment I don’t even clearly remember anymore—probably some extra duty or restriction, but the sting of the rank loss drowned it all out.

The Real Cost of a Stripe

Losing E4 wasn’t just a matter of pride—though that was a massive part of it—it was also a gut punch to my finances. The demotion cost me:

That’s $400/month gone, instantly. But more than that, it was the humiliation. I had to have all my uniforms re-sewn. Everyone knew. It was a public walk of shame in the tight-knit world of submariners.

And looming on the horizon? I was slated to be transferred to another 688-class sub, the USS Asheville. That idea haunted me—I was convinced it would break me for good. Luckily—or perhaps fatefully—I would never set foot on that boat.

Breaking Point

The demotion wrecked me. I remember sitting alone, feeling utterly dismantled. I had put so much into my Navy career—graduated in the top of my class, earned respect in my division, trained relentlessly, showed up early, stayed late.

And now? I was backstabbed by a guy who couldn’t even wake up on time... sabotaged by two bitter roommates… and finally, betrayed by a commander I believed would do the right thing.

I wanted to die. For real.

I stood in the corner of that dusty barge room, surrounded by power plant manuals, operating instructions, engineering logs… and somehow I found the Navy personnel manual tucked among them. In that thick tome was my first glimpse of hope. A small paragraph. A possibility:

"Service members facing a significant loss of rate or unsuitable assignment may apply for early separation under honorable conditions.”

That was it.

I loved the Navy—that’s the truth. But I could not continue as an E3, humiliated, ignored, and shoved into an unforgiving pipeline. I had just over two years left on my contract. And the way I saw it then—those two years would be worse than prison.

And now, with 8.5 years of real incarceration behind me, I can confirm it absolutely would have been.

A New Path Forward

Armed with the info, I went straight to the ship's newly assigned senior corpsman, our Doc. I told him flat out:

“Doc, I need to see the shrink in Oakland.”

Maybe it was my tone. Maybe it was the honesty in my eyes. Or maybe he just knew the look of a man standing at the edge. He didn’t fight me. He just nodded.

Chapter 33: Oakland, the Shrink, and the Hat Trick

The Ride to Oakland

So I hopped in the trusty red Geo Storm GSI—still bearing road grime from a dozen other cross-country stunts—and headed down to Oakland. No GPS, just intuition, a glovebox copy of the Rand McNally, and whatever rage was left to burn.

The appointment was with a senior Navy shrink, uniformed and seated behind a desk that probably hadn’t moved since Vietnam. I didn’t bother with ceremony.

I looked him dead in the eye and said:

“If you don’t let me out, I’m going to find the steepest hill I can and skate down it until I break something. Then I’m going to do it again. And again.”

He studied me for a second—leaned back a little, arms folded like he’d heard this before. Then came the reply:

“You don’t have to go through all that. I can have you out in two weeks.”

Just like that.

The Last Laugh

I drove back to the barge with the biggest grin I’d worn in months. Not out of malice—just pure, unfiltered relief. The kind that settles in your chest when you realize you aren’t crazy after all. You were just in a crazy situation.

I walked into the lounge and told everyone:

“I’m out in two weeks. Honorable. That’s right.”

To a man, no one believed me. Not a single sailor had heard of it happening. One even asked if I forged papers. I didn’t. It was real.

I pulled a hat trick—walked out of the Navy clean, with an honorable discharge, and no more Chief Whitson breathing down my neck or ELT Woods gaslighting me into a disciplinary spiral. I was free.

No Counseling, No Map

Here’s the thing though—no one gave me a transition plan. The command was stretched thin. The shipyard was a skeleton crew. And no one sat me down to explain the VA system, or that I’d be eligible for disability.

They handed me my DD-214 and waved goodbye. No exit interview. No medical review board. No acknowledgment that I’d spent the last year with a crushed ego, an eating disorder, and a spiral of sabotage.